|

|

楼主 |

发表于 2012-11-28 22:55:07

|

显示全部楼层

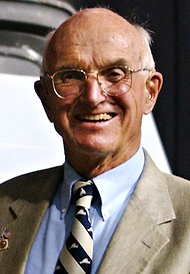

Joseph Murray, Nobel-Winning Pioneer of Kidney Transplants, Dies at 93

Nov. 27, 2012, 7:30 p.m. PST

The Washington Post News Service with Bloomberg News

(c) 2012, The Washington Post.

Joseph Murray, the surgeon who 58 years ago stitched a new kidney into a young man dying of renal failure, an operation that was recognized as the first successful human organ transplant, died Monday in Boston. He was 93.

The cause was hemorrhagic stroke, said his son Richard Murray.

Joseph Murray was one of two physicians who received the 1990 Nobel Prize in medicine for their pioneering work in transplant therapy. The other, medical researcher E. Donnall Thomas, who developed the bone marrow transplant, died in October.

In their separate fields, the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute found, the two men made discoveries that have proved "crucial for those tens of thousands of severely ill patients who either can be cured or be given a decent life when other treatment methods are without success."

Murray began his work in the late 1940s at the Boston hospital where he died, the institution then known as Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and now called Brigham and Women's Hospital. In the early years of his career, he practiced on dogs to perfect his nearly sartorial technique of sewing a donor kidney into a patient's body.

Later, he helped other researchers develop radiation treatments and drugs to suppress a patient's immune system and prevent organ rejection, the most serious complication presented by transplant procedures.

His work on kidney transplants helped lead to successful transplant techniques for other organs, including the heart, lungs, liver and pancreas. Jean-Michel Dubernard, the surgeon who in 2005 was credited with performing the first partial face transplant, said he dedicated the operation to Murray.

He was a young Army doctor when he first became fascinated by the body's ability — or refusal — to weave foreign tissue into the fabric of its own system. At Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania, he performed skin grafts on returning soldiers disfigured in combat and fires in World War II.

Sometimes, he once recalled, the skin would just "melt around the edges." The patient had rejected it. But at least one of his patients accepted the new skin. The experience left Murray hopeful about the future of organ transplantation, despite overwhelming doubt within the medical community.

Some ethicists questioned the morality of removing an organ from a healthy person to save the life of someone else. After all, they said, the Hippocratic oath required doctors to do no harm. Meanwhile, numerous patients died in the early years of organ transplants. Surgical techniques were imprecise, and doctors lacked the immunosuppressive therapies to prevent rejection.

With the surgery they performed on Dec. 23, 1954, Murray and his team of surgeons began to assuage some of those concerns. The patient, Richard Herrick, 23, was suffering from end-stage renal failure. His identical twin, Ronald, had stepped forward to offer his kidney. Because the men shared the same DNA, organ rejection was unlikely.

Joseph Murray, the surgeon who 58 years ago stitched a new kidney into a young man dying of renal failure, an operation that was recognized as the first successful human organ transplant, died Monday in Boston. He was 93.

The cause was hemorrhagic stroke, said his son Richard Murray.

Joseph Murray was one of two physicians who received the 1990 Nobel Prize in medicine for their pioneering work in transplant therapy. The other, medical researcher E. Donnall Thomas, who developed the bone marrow transplant, died in October.

In their separate fields, the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute found, the two men made discoveries that have proved "crucial for those tens of thousands of severely ill patients who either can be cured or be given a decent life when other treatment methods are without success."

Murray began his work in the late 1940s at the Boston hospital where he died, the institution then known as Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and now called Brigham and Women's Hospital. In the early years of his career, he practiced on dogs to perfect his nearly sartorial technique of sewing a donor kidney into a patient's body.

Later, he helped other researchers develop radiation treatments and drugs to suppress a patient's immune system and prevent organ rejection, the most serious complication presented by transplant procedures.

His work on kidney transplants helped lead to successful transplant techniques for other organs, including the heart, lungs, liver and pancreas. Jean-Michel Dubernard, the surgeon who in 2005 was credited with performing the first partial face transplant, said he dedicated the operation to Murray.

He was a young Army doctor when he first became fascinated by the body's ability — or refusal — to weave foreign tissue into the fabric of its own system. At Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania, he performed skin grafts on returning soldiers disfigured in combat and fires in World War II.

Sometimes, he once recalled, the skin would just "melt around the edges." The patient had rejected it. But at least one of his patients accepted the new skin. The experience left Murray hopeful about the future of organ transplantation, despite overwhelming doubt within the medical community.

Some ethicists questioned the morality of removing an organ from a healthy person to save the life of someone else. After all, they said, the Hippocratic oath required doctors to do no harm. Meanwhile, numerous patients died in the early years of organ transplants. Surgical techniques were imprecise, and doctors lacked the immunosuppressive therapies to prevent rejection.

With the surgery they performed on Dec. 23, 1954, Murray and his team of surgeons began to assuage some of those concerns. The patient, Richard Herrick, 23, was suffering from end-stage renal failure. His identical twin, Ronald, had stepped forward to offer his kidney. Because the men shared the same DNA, organ rejection was unlikely.

The procedure took 5 1/2 hours. J. Hartwell Harrison, Murray's colleague, removed the healthy kidney from Ronald Herrick. The organ was wrapped in a wet towel, placed in a stainless steel container and rushed to the operating room where Murray was waiting with Richard Herrick.

"It was marvelous," Murray told National Public Radio, recalling the moment when he saw the kidney begin to work. "It just pinked up the way we wanted, little punctated blood vessels all over the kidney surface, and they were snug as a bug in a rug."

Richard Herrick survived eight years — marrying one of his nurses and having two children — before he died of a recurrence of the disease. In that time, Murray continued to improve his surgical technique.

In 1962, he and his colleagues achieved perhaps their biggest breakthrough: the first transplant from an unrelated donor, a man who had died in heart surgery.

"Kidney transplants seem so routine now," Murray told The New York Times after he received the Nobel. "But the first one was like Lindbergh's flight across the ocean."

Murray later returned to plastic surgery, the field of medicine that first interested him in transplants. He was credited with developing procedures to repair congenital facial defects in children and once said that some facial reconstructions were more difficult than transplant surgeries. He retired in 1986.

Joseph Edward Murray was born April 1, 1919, in Milford, Mass. His mother was a schoolteacher; his father was a district court judge. He wrote in an autobiographical sketch for his Nobel Prize, that "from earliest memory," he wanted to be a surgeon, "possibly influenced by the qualities of our family doctor."

Murray received a bachelor's degree in classics from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass., in 1940 and a medical degree from Harvard University in 1943.

In the earlier years of his career, he became friends with Thomas, his fellow Nobel laureate. "It doubles the pleasure," Murray said when they received the prize. "I couldn't be happier."

His autobiography, "Surgery of the Soul: Reflections on a Curious Career," was published in 2004.

Survivors include his wife of 67 years, Virginia "Bobby" Link Murray of Wellesley, Mass.; six children, Virginia Murray and Dr. Katherine Murray-Leisure, both of Plymouth, Mass., Margaret Murray Dupont of Lafayette, Calif., J. Link Murray of Jamestown, R.I., Thomas Murray of Dallas and Richard Murray of Scituate, Mass.; 18 grandchildren; and several great-grandchildren.

In the early years of his work on transplant therapy, Murray was accused by some detractors of "playing God." He was a devout Catholic and was reported to have knelt in prayer with his family before the Herrick operation.

"Work is a prayer," he once told an interviewer. "And I start off every morning dedicating it to our Creator. "......

The procedure took 5 1/2 hours. J. Hartwell Harrison, Murray's colleague, removed the healthy kidney from Ronald Herrick. The organ was wrapped in a wet towel, placed in a stainless steel container and rushed to the operating room where Murray was waiting with Richard Herrick.

"It was marvelous," Murray told National Public Radio, recalling the moment when he saw the kidney begin to work. "It just pinked up the way we wanted, little punctated blood vessels all over the kidney surface, and they were snug as a bug in a rug."

Richard Herrick survived eight years — marrying one of his nurses and having two children — before he died of a recurrence of the disease. In that time, Murray continued to improve his surgical technique.

In 1962, he and his colleagues achieved perhaps their biggest breakthrough: the first transplant from an unrelated donor, a man who had died in heart surgery.

"Kidney transplants seem so routine now," Murray told The New York Times after he received the Nobel. "But the first one was like Lindbergh's flight across the ocean."

Murray later returned to plastic surgery, the field of medicine that first interested him in transplants. He was credited with developing procedures to repair congenital facial defects in children and once said that some facial reconstructions were more difficult than transplant surgeries. He retired in 1986.

Joseph Edward Murray was born April 1, 1919, in Milford, Mass. His mother was a schoolteacher; his father was a district court judge. He wrote in an autobiographical sketch for his Nobel Prize, that "from earliest memory," he wanted to be a surgeon, "possibly influenced by the qualities of our family doctor."

Murray received a bachelor's degree in classics from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass., in 1940 and a medical degree from Harvard University in 1943.

In the earlier years of his career, he became friends with Thomas, his fellow Nobel laureate. "It doubles the pleasure," Murray said when they received the prize. "I couldn't be happier."

His autobiography, "Surgery of the Soul: Reflections on a Curious Career," was published in 2004.

Survivors include his wife of 67 years, Virginia "Bobby" Link Murray of Wellesley, Mass.; six children, Virginia Murray and Dr. Katherine Murray-Leisure, both of Plymouth, Mass., Margaret Murray Dupont of Lafayette, Calif., J. Link Murray of Jamestown, R.I., Thomas Murray of Dallas and Richard Murray of Scituate, Mass.; 18 grandchildren; and several great-grandchildren.

In the early years of his work on transplant therapy, Murray was accused by some detractors of "playing God." He was a devout Catholic and was reported to have knelt in prayer with his family before the Herrick operation.

"Work is a prayer," he once told an interviewer. "And I start off every morning dedicating it to our Creator. "......

|

|